Originally published at The Federalist Society by Ronald A. Cass| December 16, 2014

Introduction

Criminal law is the biggest, scariest tool in the arsenal of governmental powers: it can result in loss of property, loss of freedom, and even loss of life. That theme is repeated through history and literature, as readers of Crime and Punishment,1 The Count of Monte Cristo,2 The Gulag Archipelago,3 or countless other works from countries around the world understand. Criminal law is the means by which government’s coercive power over those within its domain ultimately is effected?either through the direct imposition of criminal punishments or the threat of their imposition.4 It is also a power that is brought to bear through retrospective action; the application of criminal punishments inevitably depends on determinations of fact respecting past conduct and of the fit between facts and legal rules. Rules governing the criminal law are announced in advance, but their enforcement depends on decisions made after the conduct occurred, determining whether the conduct will be a basis for criminal prosecution, on what terms, with what energy, and ultimately whether the conduct violates the law and what punishment will be assessed.

Because it poses the gravest threat to individuals’ lives, liberty, and property, criminal law traditionally has been circumscribed in special ways. The essence of the rule of law is the reduction of official discretion to the point that exercises of official power are predictable in advance—independent of the particular official wielding that power—by those to whom the law’s power is directed.5 The development of law in nations that adhere strongly to the rule of law very largely has been built on the foundation stone formed by an accretion of rules constraining criminal power—precisely because it is the power that is essential to tyranny.6

The same appreciation is evidenced in the construction of government in the United States. The background understanding is illustrated in the justification offered by Alexander Hamilton for the special protection of trial by jury in criminal cases. Although Hamilton’s purpose in writing the essay that appeared as Federalist No. 83 was to combat assertions that the proposed Constitution abolished rights to civil trial by jury, his essay also underscored the difference those in the Framing generation saw between civil and criminal law:

I must acknowledge that I cannot readily discern the inseparable connection between the existence of liberty, and the trial by jury in civil cases. Arbitrary impeachments, arbitrary methods of prosecuting pretended offenses, and arbitrary punishments upon arbitrary convictions, have ever appeared to me to be the great engines of judicial despotism; and these have all relation to criminal proceedings.7

With that difference in mind, governments in the United States have adopted special rules that restrict the ways in which criminal sanctions can be announced, tailored, and applied. Prohibitions on ex post facto law-making (attaching criminal punishments to conduct not unlawful at the time)8 and on bills of attainder (creating special punishments for specific, identified or readily identifiable individuals),9 acceptance of special rules of procedure and burdens of proof and persuasion (for example, the presumption of innocence, protections against coerced testimony, requirements of unanimity for criminal conviction, safeguards against double jeopardy)10—all of these are devices for protecting citizens against the unchained and unchecked criminal law power of the state. So, too, is the long-standing requirement that laws be reasonably knowable in advance, either because they deal with matters of such basic morality that every sentient being can be presumed to understand the nature of the law’s prohibition (e.g., unprovoked killing, theft, assault) or because the person against whom the law is being enforced had every opportunity and incentive to know the law.11

More recently, however, both practical and doctrinal changes have significantly reduced the degree to which criminal punishment fits rule-of-law ideals. Although far from the only cause, the expansion of criminal sanctions as a by-product of an extraordinary explosion in administrative rulemaking that is backed by criminal liability has helped propel this change. While there are reasons to support criminal enforcement of administrative decision-making, the ways in which administrative rules are adopted, applied, and enforced and the scale of governmental law-making (including administrative rule-making) that has provided the grounds for potential criminal penalties have produced a massive increase in government power that risks serious erosion of individual liberty. This change cries out for immediate attention—and for changes to the law.

Admittedly, discussion of overcriminalization, like discussion of “tax loopholes,” to some extent is a matter of perspective. Many commentators have noted that a loophole is a deduction the speaker dislikes (even if those who benefit from the deduction loudly applaud it). In the same vein, any list of criminal penalties (specifically or generically) that make for the excessive use of criminal law—in other words, what constitutes the “over” in overcriminalization—certainly is debatable.12 And some scholars believe that focusing on the growing array of statutory and administrative provisions that can give rise to criminal punishment misleads in comparison to the set of cases for which charges actually are brought.13 But what should not be debatable is the understanding that a problem now exists and that its continuation threatens the rule of law.14 No matter which provisions and doctrines seem beneficial in particular settings, concern over the current state of the law—and even more, its direction—should be common ground.

This paper begins with a brief review of the contrasting approaches of criminal law and administrative law—the traditional rules of criminal law and process that provide protections against misuse of government power and the basic predicates animating delegation of authority to administrative decision-makers, circumscribing their exercise of authority, but also generally facilitating administrative exercise of authority. The paper then discusses experience with statutory and administrative rule generation and application, explaining how differences between administrative law and criminal law play out in these contexts.

Special attention is given to tensions between the bodies of law (on paper and in practice) and discretion-limiting principles associated with the rule of law. While accommodations for both administrative law and criminal law have been worked out that have been generally satisfactory—that have gained broad acceptance in the United States and other law-bound nations—modern realities increasingly have allowed exercises of power that strain the limits of the rule of law. This is particularly evident in the expansion of criminal penalties (driven in substantial part by administrative rulemaking) and of the discretionary power exercised by officials entrusted with enforcement of criminal laws. Debate focused on the frequency of prosecutions misses the point that even relatively rare applications of criminal enforcement powers can have significant effects, given the common trade-off between frequency of enforcement and magnitude not only of penalties but also of officials’ discretionary power respecting enforcement choices. Changes both to laws and judicially-constructed doctrines are needed to protect against potential abuse of government power.

I. Criminal Law and Administrative Law: A Tale of Two Cities

An enduring metaphor in American political discourse is that of the “city on the hill.” Its original use in America by John Winthrop, first Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, as well as its Biblical antecedent, denotes a place of special visibility where flaws cannot be hidden and where, hence, there is special reason for charity, compassion, and cooperation. In a similar vein, the “cities” represented by our criminal and our administrative processes, as provinces of especially important applications of government power, should be especially subject to scrutiny and, ideally, should embody the citizenry’s highest ideals for the exercise of government power. The bodies of law that undergird these two cities, however, are not the same—they address different needs, start with different predicates, and have been subject to different stresses and distortions. It is helpful to begin with the basic assumptions framing these bodies of law.

A. Predicates for Criminal Law

The primary principles that describe criminal law can be captured in a very limited set of restraints on the substance of criminal prohibitions and a relatively expansive set of limitations on the application of criminal laws.

1. Substantive Limits

Substantive constraints include proscriptions on singling out specific individuals for special punishment—the passage of bills of attainder, which the Constitution makes unlawful for the states as well as for the national government15—on imposing retroactive punishments (also constitutionally prohibited for state and national government),16 on cruel and unusual punishments,17 on vaguely defined crimes,18 and on penalties that are overbroad because they attach to constitutionally protected conduct as well as to conduct legitimately subject to criminal punishment.19 These limits on substantive criminal law essentially boil down to two basic concerns that share a single root: notice and generality.20

2. Notice

First, constitutional rules restrain uses of the criminal law that can’t be predicted by those subject to the law, who then are deprived of meaningful opportunity to conform their conduct to the law’s requirements. That is the burden of prohibitions on ex post facto laws, on vague laws, and to a large degree on overbroad laws as well, where the boundary between the permitted and prohibited cannot readily be known in advance. These are ancient requirements for criminal punishment and quintessential protections against tyranny; they were known before the time of the Roman emperors, though circumvented by Emperor Caligula’s reported practice of having his new laws written in small characters and posted high up where they were difficult to read.21 The fact that this was seen as a radical departure from accepted requirements for the law underscores the importance of notice to the legitimacy of criminal punishment. The notice concern also accounts for the recently reinvigorated rule of lenity, requiring that rules subject to criminal penalties should be construed narrowly and any ambiguity should be resolved in favor of the individual or entity charged under the law.22

3. Generality

Second, constitutional rules also restrain deployment of the criminal law in ways that either expressly place special punishments on particular individuals or are particularly likely to facilitate such special, targeted punishments. The prohibition on bills of attainder is clearly aimed at this sort of manipulation of criminal sanctions to punish those who are enemies of the officials wielding government powers. So, too, however, are restrictions on overbroad laws (where the application of the law almost certainly will be selective) and on cruel and unusual punishments (a provision that notably requires the penalty to be not only especially harsh but also uncommon).23 As with notice requirements, generality requirements are important protections against tyranny: when sauce for the goose also is sauce for the gander, ganders are far less inclined to be throwing geese in the pot.24

4. Process Limits

In addition to the nature of the laws themselves, the process of applying the criminal law traditionally has been subject to a substantial number of rules designed to prevent wrongful convictions and to restrain abuses of discretion by those charged with enforcing the law.

5. Combatting Wrongful Convictions

One of the elementary observations every first-year law student hears is that society views the risks of wrongful convictions and wrongful acquittals as asymmetrical, with conviction of the innocent carrying greater social weight. This asymmetry explains a great many special rules of criminal procedure. A non-exhaustive list would include the following: criminal convictions, unlike civil jury verdicts, require unanimity; defendants are presumed to be innocent, so the prosecution bears the burden of persuasion and the burden of proof; defendants have the right to decline to provide testamentary evidence; potentially prejudicial information (respecting matters such as a defendant’s prior convictions) is kept from jurors. In all these respects, the playing field in criminal processes is tilted in favor of the accused.

6. Restraining Discretion

The other leg of limits on criminal law enforcement targets abuse of discretion. Safeguards such as the prophylactic Miranda rule specifying particular sorts of warnings to suspects (restricting the way police can gather evidence),25 the Brady requirement that prosecutors share exculpatory evidence (which limits discretion in the characterization of available evidence),26 the prohibition on double jeopardy (which prevents strategic decisions on what evidence to utilize and restricts game-playing in trials),27 and the guarantee of a speedy and public trial (which constrains manipulation of the timing and conduct of trials)28 can be seen as efforts to restrict possible abuses of law enforcers’ discretionary choices. If everyone receives the same warnings, the same evidence, and the same protections against manipulative re-trials, the range of opportunities for abuses of law enforcement discretion is reduced.

The system does not, of course, eliminate discretion. Indeed, one of the central attributes of the criminal law system as traditionally conceived is the assignment to law enforcement officials of discretion not to pursue particular suspects, not to arrest or charge them, and not to prosecute. The law does not incorporate a requirement that all crimes are investigated, all suspects are pursued, or all persons who seem likely to have committed crimes are prosecuted. No one would want to require prosecution or arrest of individuals who, after inquiry, seem not to have committed a crime, or seem not to have had the requisite state of mind to satisfy elements of the crime, or whose circumstances make the crime less blameworthy (for example, the 96-year-old great-grandmother who shoplifts a can of tuna).

Prosecutorial discretion is defended principally on two grounds. The first is pragmatic: law enforcement resources are invariably finite and, in any society with more than a very small number of crimes choices must be made respecting the way to use those resources.29 The second justification for prosecutorial discretion is grounded in the concept of legality.30 Officials charged with investigation and prosecution are separated from those charged with evaluating the case against an accused; conduct of law enforcement officials in deciding which cases to bring (especially which not to bring) is checked by their supervisors or by the public that selects officials who are ultimately responsible, while the decision to bring charges is checked by the requirement that prosecutions must pass scrutiny from officials (and private citizens) who are not subject to the same personal or political imperatives. In other words, bring a bad case, you lose, and you may also lose favor with your bosses or the public for wasting public resources.

In the end, law enforcement discretion is retained as essential to the functioning of a system where complex judgments are needed, but the whole thrust of the system (at least at the level of legal doctrine) is to constrain, channel, and check discretion to guard against the sorts of serious problems that can arise where personal liberty, property and even life are at risk.31

B. Predicates for Administrative Law: The Basics

The basic predicates for administrative law look very different from those underlying criminal law: in contrast to the more “target sensitive” character of criminal law predicated on concerns about potential misuse of government power, administrative law places greater emphasis on providing leeway for agencies to implement laws within their purview in ways the implementing officials think best. If criminal law leans toward restraining conduct that expands the chances for punishments that respond to particular officials’ inclinations regarding individual enforcement targets or that are less readily anticipated by those subject to the law, administrative law leans toward providing scope for official judgments within a broad legal framework.

Administrative law is not concerned in the main with extraordinary impositions on individual citizens. Instead, its domain is the set of procedures appropriate to the functioning of government agencies with broad mandates to facilitate conduct that is seen as publicly beneficial (encouraging conservation efforts or public health initiatives or promoting innovation through award of patents, for example), to move resources more directly toward uses that are desirable (supporting labor training programs or infrastructure building or repair or providing direct assistance to specific beneficiaries, as with programs such as Social Security, Medicare, or various programs for military veterans), or to regulate activities that can conflict with public interests (an endless list of mandates for the “alphabet” agencies: the CPSC, FCC, FERC, FTC, ITC, SEC).

The difference between the two fields follows from the difference in their focus. The fundamental character of one body of law is mostly restraining, the other mostly enabling.

This does not mean that administrators are free simply to do as they like. As with criminal law, administrative law imposes a variety of constraints on official action, both substantive and procedural. Agency action must be authorized by particular statutes, and the first constraint on administrative officials is found in the terms of the laws that set the limits around specific administrative action.

Apart from specific enabling legislation, the law contains numerous generally applicable rules for proper performance of administrative functions?including, for example, mandated separation of certain functions,32 procedural requirements for making administrative rules and for adjudicating disputes within an agency’s purview,33 and provisions for making information held by an agency publicly available (through open meetings or ex post disclosures).34 Much significant agency action follows from rulemaking proceedings that are designed to resemble legislative processes or from adjudicative proceedings that are more or less similar—at times, quite similar—to those followed in courts. And most administrative action also is subject to scrutiny both within the agency and, if it is significant, by others through the executive review process (run through the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs), various mechanisms for inter-agency coordination (which can perform roles similar to, though not formally constituting, review), and judicial review.35

1. Imaginary Limits on Real Power

Procedural requirements and review can provide powerful constraints on official power. But the constraints only work to the extent that they in fact provide effective limits on agency actions. While some of the ways in which official authority is restricted provide meaningful checks, and in select instances have been very important sources of limitation, more often the obstacles to untoward exercises of official discretion have proved speed bumps instead of stone walls.

2. Nondelegation

One of the potentially most important restraints on official discretion is the “nondelegation doctrine.” The doctrine sensibly states as “a principle universally recognized as vital to the integrity and maintenance of the system of government constrained by the Constitution” that “Congress cannot delegate legislative power.”36 This straight-forward interpretation of Article I, Section 1’s declaration that “ legislative power” granted by the Constitution “shall be vested in a Congress” makes perfect sense, but has made little difference to the scope of authority given to other officials. The case that gave the classic formulation to the doctrine, Field v. Clark, approved a law giving the President the power to impose duties on a variety of imported goods “for such as time as he shall deem just” if and when he decided that the nations exporting those goods treated imports from the U.S. in a “reciprocally unequal and unreasonable” manner—hardly a precise or constraining directive.37

The Supreme Court also has approved numerous other delegations of authority on the ground that the assignments were not of legislative power but of administrative authority, even if they give extraordinary scope for policy choices by administrators, such as the instruction for the FCC to hand out licenses to spectrum users “as the public convenience, interest or necessity requires.”38 The test is whether the Court divines in the governing law “an intelligible principle to which the person or body authorized to [act] is directed to conform.”39 As the Court’s decisions over the past century make clear, “intelligible” does not mean that Congress has done the hard work of deciding what competing public interests should be taken into account, much less the harder work of resolving the inevitable differences among them.40

3. No Delegation

Similarly, courts might constrain administrative discretion by narrowly construing the ambit of authority granted to the agencies. In particular, courts might insist on very clear delegations of authority to an agency to act in respect of a particular matter—to assert general authority to address a given topic, to direct its actions to a given set of enterprises or activities, to embark on a particular course of regulation (rate-setting, for example)—even if the lack of a meaningful nondelegation doctrine does little to put bounds around the actual terms of the authorization Congress gives the agency. This occurs on occasion.41 But courts also have allowed agencies to assert authority over matters when there was no express grant of authority, even confirming agency authority so unclear that the agency had denied it had that authority and had sought unsuccessfully to attain express congressional authorization before changing course and asserting that the authority had existed all along.42

For instance, for many years the FCC denied it had authority to regulate cable television, which fit neither within the grant of authority over telephone and telegraph wire common carrier functions nor within the grant of authority over allocation of spectrum use by radio, television, and other over-the-air services. When the FCC failed to get Congress to grant authority over the burgeoning cable TV industry, it discovered that the authority existed anyway under an administrative analogy to the Constitution’s “necessary and proper” clause—no matter how unnecessary or improper the actual regulations. The Supreme Court approved the assertion of authority under a very questionable rationale, an approval that has encouraged further efforts to extend FCC authority ever since.43

Just as the current version of the nondelegation doctrine grants Congress substantial room to assign scope for discretionary policy choices to administrators, courts commonly allow leeway for agencies to exercise discretion in determining the scope of their assignments.44

4. Deference

Perhaps the clearest example of the leeway given to administrative officials generally is encapsulated in the Chevron doctrine.45 Chevron declares that, when agency action is challenged as inconsistent with its statutory instruction, courts ask first if Congress has “directly spoken to the precise question at issue.” If so, that is binding; if not, courts are directed to defer to any reasonable agency interpretation of the law.46 The assumption behind Chevron deference is that courts would have to defer to administrative policy choices if Congress expressly gave authority to make such choices to the agency; by analogy, the Court stated that Congressional failure to specify a precise answer to a policy question can constitute an implicit delegation of authority.47 Judicial failure to defer to reasonable agency interpretations of law in such settings would overstep judicial bounds.48

The Supreme Court has argued endlessly over details of the Chevron test and its application, and it has referred in some cases to older tests for deference as well.49 Scholars have argued over whether Chevron has raised even further the traditionally high degree of deference given to administrative decisions and whether the costs of litigating (and anticipating) applications of the Chevron rule are worth whatever is gained in administrative efficiency or fidelity to law.50 But the bottom line is that under any of the iterations of the deference canon, judges generally have been supportive of administrative exercises of discretion even on questions that are so close to the law-interpreting role assigned to courts as to be virtually indistinguishable.

II. Law-Making, Administration, and Prosecution

Differences between the two bodies of legal doctrine described above respond to different expectations about the critical function to be served by each. The divergence in expected orientation of criminal and administrative law—between focusing on specific conduct so outside the realm of the acceptable as to be criminal and focusing on handing out benefits to large numbers of recipients, processing patent applications or tax returns, licensing pipelines or television stations, regulating food and drug offerings, and the like—is reflected in different expectations about rule-generation. Differences in the visibility and frequency of rule-generation also have important implications for the acceptable means of giving rules effect, of the sorts of mechanisms appropriate to assure compliance with them. Use of the criminal law, as shown below, to enforce an expanding array of administrative rules has unfortunate consequences.

A. Rule-Generation

1. Law-Making and Rule-Making

The initial difference so far as rule generation goes is that rules setting out the basis for criminal sanctions traditionally have been products of legislative enactments.51 Administrative rules, on the other hand, have dealt with all sorts of specifications of what those subject to the particular agency’s jurisdiction must do or not do, how the agency will conduct its business, what its interpretation of its governing mandate is, or how it balances policy considerations urged as relevant to resolution of a specific problem.

The two sources are not equally suited to quick or prolific rule-generation. Despite recent complaints about “gridlock” and the fact that the Framers self-consciously designed the U.S. Constitution to be more amenable to decisive action by the national government within its allotted sphere, the Constitution also was very much devised as a governance regime whose combination of checks and balances were calculated to inhibit action that did not have strong support across a variety of political sources and regions. In other words, it was intended to delay action until it had been carefully considered, to frustrate tyranny of the majority as well as of smaller factions.52 The default position was, thus, for the national government to take no action.

In contrast, administrative rule-making is designed to be relatively expeditious, with “some action” instead of “no action” as the norm. There are relatively few procedural requirements, and these mainly were conceived as modest prods to fair and effective government rather than as high hurdles that agencies would surmount only with considerable difficulty.53 The public pronouncement initially required of agencies proposing rules was not an elaborate advance explanation and lengthy marshaling of evidence but a simple notice of “either the terms or substance of the proposed rule or a description of the subjects and issues involved.”54 Similarly, the rule itself did not need a full explication of its operation but only “a concise, general statement of [the rule’s] basis and purpose.”55

As the subjects committed to agency rule-making have expanded and the magnitude of the effects from agency rule-making have increased, additional requirements—judicial, legislative, and executive—have been layered on top of the initial ones, leading some commentators to complain that federal rule-making had become “ossified” and unworkable.56 Undeniably some new and significant requirements have been added to what agencies must do in rulemaking, including those imposed by the Paperwork Reduction Act, the Regulatory Flexibility Act, and the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act.57 But other, much discussed demands on the agencies are not formally necessary to rulemaking. For example, courts at times have asked for more complete explanation of the basis for a new rule when reasons given in support of the rule did not counter objections that were supported by substantial information in court filings.58 In other words, these were not general requirements for making rules but evidentiary requirements for justifying rules once the initial burden on the party challenging the rule was met.

For rules of major economic or political importance, the difference may be slight in practice,as there is apt to be a challenge backed by substantial information about the weaknesses of such rules in virtually every case, but that does not affect the vast majority of rules—and it isn’t terribly unreasonable to expect that when rules have a major economic impact, the officials adopting them should be able to explain the rules’ basis in something other than conclusory terms. However, for government agencies imposing burdens on others than can run to billions of dollars annually, it seems entirely sensible to expect something more than the equivalent of “because I’m your mother and I say so!”

2. Laws, Rules, and Crimes

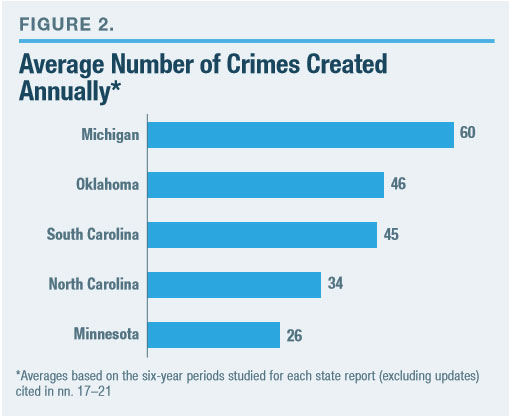

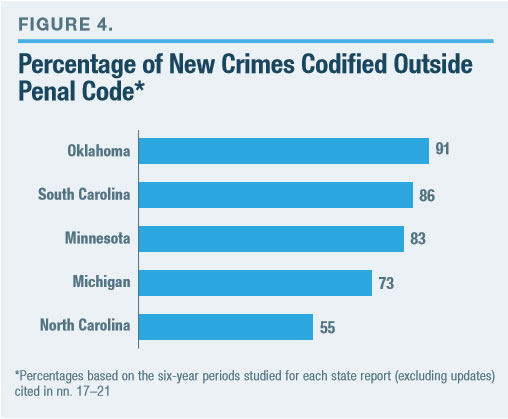

Despite the increased justification required for rules, at least in some settings, there has not been a real rulemaking deficit. In fact, rules have been pouring out of federal agencies for decades. Federal agencies issue between 3,000 and 5,000 new rules in a typical year, covering between 20,000 and 40,000 pages annually in the Federal Register.59 In comparison, Congress typically passes between 200 and 400 laws each year, though outliers have varied significantly on either side of those figures.60

This disparity in rule-creation poses special problems in connection with criminal law, dramatically exacerbating the issues associated with large numbers of federal crimes. The exact numbers are disputed—and almost certainly unknowable with any degree of precision—but it is clear that the number of provisions that carry criminal punishment has grown dramatically over the past 50 years, and especially over the past 25 years.61 The increase has come partly from increasing resort to criminal penalties in statutes. Estimates of the number of federal laws containing criminal sanctions generally place the figure in the range of 4,000-5,000.62 The (primarily political) reasons behind the increasing use of criminal penalties have been explored by others;63 for present purposes, it suffices that the pressures for criminalizing a range of activities—including considerable conduct about which views on propriety, much less criminality, differ?and for bringing an expanded array of crimes within the federal sphere do not seem to be abating.

Even as statutory criminal provisions are proliferating, far more new rules backed by criminal sanctions have come from administrative bodies. The number of criminally-enforceable, administratively-generated rules is estimated at between 10,000 and 300,000.64 Such a wide spread in the estimates indicates that there are different ways of counting—entire rules, for example, versus separate provisions that contain prohibitions of, or requirements for, particular actions, each backed by potential criminal liability. By way of comparison, one review puts the number of “individual regulatory restrictions” contained in existing federal regulations at more than one million,65 a figure that would make the larger number of criminally enforceable rules understandable as separate regulatory requirements, rather than entire rules. It also suggests that roughly a third of all federal regulatory requirements are enforceable through criminal prosecution, a staggering number for a system of administrative rule-making that is built on flexibility for and deference to decisions of unelected officials.

Whatever the exact number of rules, it is clear that finding all federal criminal provisions would require a truly daunting search. If focused strictly on statutory enactments, the search would cover 51 titles and more than 27,000 pages of the U.S. Code, while looking for the whole body of potential criminal offenses flowing from administrative regulations would necessitate going through nearly 240 volumes of the Code of Federal Regulations spread across roughly 175,000 pages—and that was as of four years ago!66 Even for speed-readers who can master turgid prose and have a taste for tedium, that’s quite a research project.

B. Rule-Application

The enormous size of the corpus of legal materials containing federal criminal laws and administrative rules with the force of law, wholly apart from any sources of authoritative explanations or interpretations, has substantial impact on the way the federal criminal law should be applied—think of this as what follows when the skinny high school kid balloons into a sumo-size grown-up. Two sorts of problematic prospects in particular follow from the way this body of criminal law has grown: penalizing the reasonably unaware and expanding discretion for law enforcers. Both of these developments threaten the rule of law.

1. Ignorance of Law in a Law-Rich World

First, conviction under the criminal law traditionally has required that the defendant either know or should have known that his conduct violates a legal requirement. So, for example, common law crimes in Anglo-American law—such as murder, mayhem, rape, robbery, assault, or arson—required behavior combined with intentionality that together so obviously violated accepted norms of behavior as to give fair warning of what conduct would prove criminal. Where statutory crimes were not defined in ways that gave similar notice, as happens where criminal laws are vague, judges customarily have held that conviction under the laws violated standards such as due process or the Sixth Amendment’s requirement of notice of the nature of the accusation being made.67 The notion is captured by Justice Sutherland’s observation, writing for the Supreme Court in rejecting criminal charges for a government contractor accused of paying wages too low in relation to those “prevailing” in the “locality:”

That the terms of a penal statute creating a new offense must be sufficiently explicit to inform those who are subject to it what conduct on their part will render them liable to its penalties is a well recognized requirement, consonant alike with ordinary notions of fair play and the settled rules of law, and a statute which either forbids or requires the doing of an act in terms so vague that men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application violates the first essential of due process of law.68

In the same vein, judges have remonstrated that “men of common intelligence cannot be required to guess at the meaning of” a criminal law.69

Most discussion of the issue of “fair warning” has focused on the degree to which laws are written clearly enough to pass muster. But other cases have turned to questions apart from the actual statutory text. On occasion, courts have asked how much uncertainty in a law’s text can be cured by explication of its meaning by courts or other authoritative sources.70

Judges also have asserted that requirements of criminal intent can cure vagueness, as where the law requires that a defendant has “willingly” or “intentionally” engaged in conduct.71 Certainly, eliminating mental states (some form of intentionality) as elements in criminal law can aggravate “fair warning” problems. If the conduct is not sufficiently well defined to satisfy the “fair warning” requirement, however, the fact that the conduct actually engaged in was intended cannot provide notice that the conduct is criminal.72 Knowing that you’re doing something and intending to do it is not the same as knowing that what you are doing is criminal and intending to do it anyway.

This moves us closer to the heart of the problem: the more serious issue usually is not the clarity of the law standing alone but whether there was a reason to expect the defendant to have known of the law in the first place. Taking these issues together, the question is whether there is a reason for the defendant to have known that the law applied to the sort of conduct that the defendant contemplated. The assertions made in numerous cases today are that it is not reasonable to interpret a rule in a given way and, in the event the disputed interpretation is adopted, that the defendant should not be charged with responsibility for a violation he could not have foreseen.

That is the claim, for example, in Yates v. United States, which will be argued next Term in the Supreme Court.73 Yates, who operates a fishing boat, was charged under a provision of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act74 for throwing several red grouper (possibly measuring less than 20 inches long) overboard to prevent federal officials from proving that his crew had caught undersize fish. The provision, titled “Destruction, Alteration, or Falsification of Records in Federal Investigations and Bankruptcy,” applied to anyone who “knowingly alters, destroys, mutilates, conceals, covers up, falsifies, or makes a false entry in any record, document, or tangible object with the intent to impede, obstruct, or influence the investigation or proper administration of any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of the United States . . .”75 Yates argues that it isn’t reasonable to view the law as applying to someone throwing fish overboard as opposed to shredding or destroying documents (whether on a computer or on a physical medium such as paper or a disk). He also says that it isn’t reasonable to expect a fishing captain to know the details of Sarbanes-Oxley, a 66-page long act introduced as the “Corporate and Auditing Accountability, Responsibility and Transparency Act of 2002,” codified at various sections scattered across the U.S. Code.

The courts frequently reject assertions such as Mr. Yates’ by invoking the maxim that ignorance of the law does not excuse, but the doctrine makes far less sense in the current, law-rich world than when laws were largely congruent with morality, were widely known to everyone in the community (or everyone likely to encounter the law), or reasonably should have been known by someone in a profession or business as a rule specifically applying to that profession or type of business.76 When there are tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of rules backed by criminal punishment, it is unrealistic to suppose that enforcement targets know all of them.

Ordinary citizens almost certainly have no idea of many of the criminal prohibitions and criminally-sanctioned requirements they might encounter, and even businesses that use highly paid legal counsel may not be able to keep up with all of the rules and regulations that could apply to them. The much-criticized Lacey Act, which criminalizes trade in wildlife or plants that were taken in violation of state, tribal, or foreign law,77 is just one example of a law that almost certainly makes criminal conduct that almost no one could predict. Its core may be prevention of conduct that is visibly unlawful—poaching alligators in Florida for sale in New York or trading in ivory from illegally taken elephant tusks—but the full scope of conduct made criminal under the law is almost unfathomably large.78 While commentators and judges have proffered several reasons to support the ancient maxim on ignorance, none sensibly justifies extending criminal punishment to individuals who are reasonably unaware of the law.79 In a world where the scope of criminal law is so amazingly large, most of us are reasonably unaware of a great deal that could land us in jail.

2. Implications for Prosecutorial Discretion

The ultimate response to concerns of overcriminalization is that prosecutors will not bring charges against the reasonably unaware, but instead will spend their time targeting people and enterprises that are engaged in conduct known to be unlawful. One defense of current law starts with the proposition that federal criminal law is the tail of criminal enforcement and that everything other than cases involving drug offenses, immigration, and weapons charges lies at the tail of federal enforcement.80 Concerns about charges based on odd or unknowable laws—use of Woodsy Owl’s or Smokey the Bear’s likeness, for example, two of the many crimes listed in the American Bar Association’s report on the federalization of criminal law81—assertedly are exaggerated because federal prosecutors are as unlikely to know (and to try to use) those laws as defendants are to know them.82

The problem of prosecutorial discretion in a world with such massive numbers of criminal prohibitions and regulations, however, is not that there is apt to be a surge in prosecutions for trivial or obscure crimes. Instead, the problem is that prosecutors, who enjoy the option of choosing whom to charge with which crime and how many crimes to charge, now are given so expansive a range of potential charges that their discretionary power is greatly magnified.83 Imagine that you’re a student facing an important test; you know 70 percent of the questions will come from three important chapters in the book; the rest of the questions will come from the remaining material referred to during the course. Does it matter if that material covers 175 pages or 175,000 or 1.75 million pages? Does it matter if the teacher gets to select not just the questions but which students will be asked to take the test? I have no doubt how my high-school-age daughter and her friends would answer those questions.

Having the opportunity to select enforcement targets and to charge them with a very large number of crimes with potentially huge cumulative penalties gives prosecutors a weapon not all will use and in all likelihood none will use routinely. The defendants who are on the receiving end of such charges may be selected for reasons that seem laudable; the prosecution and conviction of Al Capone for tax evasion, for example, was widely applauded. There may be good reason to accept the assurance that prosecutors in general will behave in ways that are consistent with reasonable expectations.

But a focus on the typical rather than the possible—a good analytical instinct in many instances—misses the most important point here. Giving a set of government officials such a potent weapon, one that they are likely to deploy against a very small subset of possible targets, creates a dramatic opportunity for discretionary choices to be made on less attractive bases.84 Where enforcement is necessarily highly selective, penalties often will have to be increased if enforcement is to be effective; this means that a few people or entities will be charged with crimes for which high penalties are possible but for which most offenders will not be prosecuted.

Further, highly selective enforcement, if it is to affect underlying behavior, cannot reveal the bases on which enforcement targets will be selected—imagine the IRS announcing which deductions of what magnitude will cause the agency to audit tax filers. The result is that the basis for selecting a small number of potential targets for prosecution is not visible to, or predictable by, the public. That sort of discretion, which is largely insulated from significant sources of constraint in individual cases, is antithetical to the rule of law. 85

The problem is even greater than might first appear, thanks to other features of the current criminal law system. The ability to threaten defendants with multiple charges, many involving few defenses of the sort common in traditional crimes (defenses keyed to absence of culpable mental states, for example), and to confront them with a risk of staggering potential prison time or financial cost or both, allows prosecutors to pressure defendants to settle rather than to fight, to enter a plea bargain that admits guilt (whether it truly existed or addressed conduct that was truly wrongful in any meaningful sense), and to take a small punishment.86

Worse yet, if the risk is large enough—if the penalties that are threatened are sufficiently draconian—and the costs of litigating high enough, defendants might accept quite harsh punishment, even when they believe they’ve done nothing wrong and are confronted with criminal charges of which they’ve had no fair warning.87 The real issue in the Yates case is not whether the defendant did something wrong; it’s whether the prosecutor should have free rein to charge a crime that seems so far removed from the conduct at issue, one drawn from a law targeting corporate accounting, not catching undersized fish. What is even more unusual than the charge in the Yates case is that the defendant found an ally to help fight the government, where the overwhelming majority of defendants settle to avoid the cost and risk of contesting these cases.88

The increase in plea bargains in place of trials has another downside: it reduces the effective check on prosecutors. The defense of prosecutorial discretion historically has been both its necessity in a world of limited resources and its subjection to the check of judicial processes for cases that go forward. As the number of cases that go through the judicial process dwindles, that argument loses force. Prosecutors are free to bring charges without having to prove them in court. Of course, wholly baseless charges that cannot be sustained are not likely to exert much pressure on defendants; but arguably sustainable charges, even if based on weak and contestable grounds, combined with a large number of charges with at least a slight prospect of success can suffice to pressure defendants to settle. High potential costs of litigation combined with some risk of conviction and huge potential penalties often are enough to do the trick.

III. Conclusion

Growing numbers of federal crimes, driven largely by the immense number of administrative rules that are criminally enforceable, have created a serious problem for anyone committed to the rule of law. The typical prosecution may be justified and the typical prosecutor may be well behaved, but changes in the law have increased the risk of prosecutors bringing charges against people who have done nothing wrong, or nothing seriously wrong—nothing that traditionally would have been thought of as criminal—and selecting the number and nature of charges in a way that puts extraordinary pressure on defendants to agree to a plea bargain.

The morphing of administrative law doctrines (which are relatively deferential to exercises of government power) with criminal law (which long was characterized by skepticism of assertions of government power and by rules designed to constrain that power) has reduced historic protections for criminal defendants. It particularly has diminished prospects that defendants will be protected against charges of violating rules that are neither self-evident nor matters a given individual reasonably should be expected to know, the requirement of “fair notice” that repeatedly has been acclaimed as an element of due process.89

Courts do not need to require actual knowledge of criminality to make the “fair notice” concept meaningful, but they do need to recognize that without knowledge or culpable ignorance “fair notice” is a myth. By the same token, Congress should place clear limits on the power it gives administrative officials to create criminally-enforceable rules. However much observers may applaud a given use of administrative rulemaking and criminal enforcement, it is critical to understand the growing risk to liberty from giving officials unchecked power to use the criminal law by selecting from an open field of potential charges as they see fit. Attention to small risks—not complacency that they have yet to materialize—is the legacy of aspiring to be the “city on the hill” envisioned by those who lay the foundations for our nation.

Endnotes

1 Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment (Constance Garnett trans., Penguin Books 1952; orig. pub. 1866).

2 Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte-Cristo (Robin Buss trans., Penguin Books 1996; orig. pub. 1844-1845).

3 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (Thomas P. Whitney trans., Harper & Row 1973).

4 In fact, many legal theorists of widely divergent governing views and values agree that the essence of positive law is its coercive nature. See, e.g., John Austin, The Province of Jurisprudence Determined 5-21 (Legal Classics Library 1984; orig. pub. 1832); Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to The Principles of Morals and Legislation 330-31 (Hafner Press 1948; rev. ed. orig. pub. 1789); Robert M. Cover, Violence and the Word, 95 Yale L.J. 1601 (1986).

5 See, e.g., Ronald A. Cass, The Rule of Law in America 4-19, 28-29 (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press 2001) (Rule of Law); Michael Dorf, Prediction and the Rule of Law, 42 UCLA L. Rev. 651 (1995); Lon Fuller, The Morality of Law 33-94, 209-19 (Yale Univ. Press, rev. ed. 1969); Friedrich A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom 80-92 (Univ. Chicago Press 1944); Michael Oakeshott, The Rule of Law, in On History and Other Essays 119 (Barnes & Noble Books 1983); Joseph Raz, The Authority of the Law: Essays on Law and Morality 213-14 (Clarendon Press 1979).

6 For example, Magna Carta, the precursor to much of modern thinking about constraints on public power, deals primarily with limitations on powers to take property (a matter then of urgency to the feudal lords who extracted concessions from a very unenthusiastic King John, though of much less interest to the mass of English subjects) and powers to punish those deemed to have offended the King or the King’s law.

7 The Federalist No. 83 (Alexander Hamilton).

8 See U.S. Const., art. I, §§ 9-10.

9 Id.

10 See, e.g., U.S. Const., amends. V & VI.

11 See, e.g., Lambert v. California, 355 U.S. 225 (1957). The understanding that everyone reasonably should have a sense that certain conduct is subject to criminal penalties (or at least that the conduct of the person putatively subject to the particular penalties might incur criminal sanctions), in fact, provides the strongest rationale for the maxim that ignorance of the law does not excuse. See, e.g., Ronald A. Cass, Ignorance of the Law: A Maxim Re-examined, 17 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 671 (1976) (Ignorance of Law).

12 See, e.g., Sara Sun Beale, Too Many and Yet Too Few: New Principles to Define the Proper Limits for Federal Criminal Jurisdiction, 46 Hastings L.J. 979 (1995); William Stuntz & Daniel Richman, Al Capone’s Revenge: An Essay on the Political Economy of Pretextual Prosecution, 105 Colum. L. Rev. 583 (2005); George Terwilliger, III, Under-Breaded Shrimp and Other High Crimes: Addressing the Over-Criminalization of Commercial Regulation, 44 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1417 (2007); Daniel Uhlmann, Prosecutorial Discretion and Environmental Crime, 38 Harv. Envtl. L. Rev. 159 (2014).

13 See, e.g., Susan R. Klein & Ingrid B. Grobey, Debunking Claims of Over-Federalization of Criminal Law, 60 Emory L.J. 1 (2012).

14 See, e.g., Sanford Kadish, The Crisis of Overcriminalization, 7 Am. Crim. L. Q. 17 (1968); Terwilliger, supra. Not every observer, however, would concur that the problem in criminal law is “overcriminalization.” See, e.g., Klein & Grobey, supra.

15 See U.S. Const., art. I, §§ 9-10.

16 Id.

17 See U.S. Const., amend. VIII. Apart from a restriction on punishments that are deemed so extreme and so rare that the imposition is almost certain to be used only against specially disfavored targets, the restraint has been interpreted as requiring that punishments be proportional to the crime for which they are prescribed, a test that, controversially, turns on existence of a “national consensus.” See, e.g., Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407 (2008).

18 See, e.g., Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville, 405 U.S. 156 (1972).

19 See, e.g., Coates v. Cincinnati, 402 U.S. 611 (1971).

20 Not surprisingly, these also are frequently cited as critical inputs to morally justified punishment. See, e.g., Fuller, supra, at 46-55, 157-58. These concerns also are often married to concerns about legality (a sense that the proper authority has been the source of the law), but that issue is dealt with separately below in the context of limits on the procedures for enacting and applying criminal laws. For an introduction to the concept of legality and its relationship to other sources of constraint on criminal law, see, e.g., John Calvin Jeffries, Jr., Legality, Vagueness, and the Construction of Penal Statutes, 71 Va. L. Rev. 189 (1985) (Legality).

21 See, e.g., 1 William Blackstone, Commentaries *46.

22 See, e.g., Burrage v. United States, — U.S. — (2014). Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor concurred in the decision specifically on the basis of the rule of lenity (one element of the majority opinion), id., and Justice Scalia long has argued for a reinvigorated version of this rule, see, e.g., Bryan v. United States, 524 U.S. 184, 205 (1998) (Scalia, J., dissenting); United States v. O’Hagan, 521 U.S. 642, 679 (1997) (Scalia, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). Not all commentators agree that the rule either is well-considered or is observed much save in the breach. See, e.g., Jeffries, Legality, supra; Dan Kahan, Lenity and Federal Law Crimes, 1994 Sup. Ct. Rev. 345 (1994).

23 See, e.g., Harmelin v. Michigan, 501 U.S. 957 (1991) (Scalia, J.).

24 I know: ganders don’t eat geese and vice versa, though there might be a peck here or there in the yard. It’s just a metaphor riding on an aphorism.

25 See Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). See also Dickerson v. United States, 530 U.S. 428 (2000).

26 See Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963).

27 See U.S. Const., amend. V.

28 See U.S. Const., amend. VI.

29 See, e.g., Sarah Cox, Prosecutorial Discretion: An Overview, 13 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 383 (1976); Robert Misner, Recasting Prosecutorial Discretion, 86 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 717 (1996).

30 See, e.g., Misner, supra (explaining the legislative abdication of hard choices to prosecutors respecting what laws mean and which criminal provisions are directed at what specific conduct, especially emphasizing instances in which multiple criminal provisions arguably address the same conduct).

31 For a thoughtful treatment of two different models of the criminal process, one based on effective crime control, the other on legal constraints that protect individual liberties, see Herbert L. Packer, The Limits of the Criminal Sanction 150-260 (Stan. Univ. Press 1968). Professor Packer concluded that many features of our criminal process sound like the second model (what he calls “The Due Process Model”) in terms of legal doctrine, but function more like the first (what he refers to as “The Crime Control Model”). Id. at 174. It should be noted as well that acceptance of the necessity of a degree of discretion in the criminal enforcement system is not equivalent to endorsement of the degree that exists at present or its exercise by particular government officials or classes of officials.

32 Although administrative agencies often exercise a variety of functions, all combined under the aegis of the agency head (in multi-member bodies, the collective decision-making group of agency members), critically, the individuals who perform functions that might be compromised if combined (such as prosecuting and adjudicating where significant individual claims are at issue) generally are separated and, in formal adjudication, substantially insulated from controls that might compromise their fairness (perhaps even more than reasonable notions of fairness require). See, e.g., Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. §554(d).

33 See id., at 5 U.S.C. §§553-557.

34 See, e.g., Freedom of Information Act, codified at 5 U.S.C. §552; Government in the Sunshine Act, codified at 5 U.S.C. §552b.

35 See, e.g., Ronald A. Cass, Colin S. Diver, Jack M. Beermann & Jody Freeman, Administrative Law: Cases & Materials 97-103,112-229 (6th ed., Wolters-Kluwer Law & Business 2011) (Cass, et al., Administrative Law).

36 Field v. Clark, 143 U.S. 649, 692 (1892).

37 Id., at 680.

38 See, e.g., National Broadcasting Co. v. United States, 319 U.S. 190 (1943).

39 Hampton & Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 394, 409 (1928) (laying down the “intelligible principle” test and applying it to uphold delegation of broad authority to the President and Tariff Commission to set tariff rates, formerly a legislative function).

40 See, e.g., Whitman v. American Trucking Assns., Inc., 531 (U.S. 457 (2001); Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361 (1989); Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414 (1944). For a review of the doctrine more generally, see, e.g., Cass, et al., Administrative Law, supra, at 16-33.

41 See, e.g., Food & Drug Administration v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120 (2000).

42 See, e.g., National Cable & Telecommunications Assn. v. Brand X Internet Services, 545 U.S. 967 (2005); United States v. Midwest Video Corp., 406 U.S. 649 (1972); United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., 392 U.S. 157 (1968).

43 The initial Supreme Court approval of authority over cable television is United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., 392 U.S. 157 (1968). For more recent discussion of FCC efforts to expand its ambit of authority, see, e.g., Verizon v. Federal Communications Commn., No. 11-1355 (D.C. Cir. 2014); Comcast Corp. v. Federal Communications Commn., 600 F.3d 642 (D.C. Cir. 2010).

44 For an example of this deference formally applyingthe Chevron doctrine discussed below, see City of Arlington v. Federal Communications Commn., Nos. 11-1545 & 11-1547 (U.S. Sup. Ct., May 20, 2013).

45 See Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 476 U.S. 837 (1984).

46 Id., at 842-43.

47 Id., at 843-45.

48 For a more nuanced, but generally sympathetic, account of Chevron deference, see, e.g., Antonin Scalia, Judicial Deference to Administrative Interpretations of Law, 1989 Duke L.J. 511 (1989).

49 See, e.g., Entergy Corp. v. Riverkeeper, Inc., 129 S. Ct. 1498 (2009); Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, 549 U.S. 497 (2007); National Cable & Telecommunications Assn. v. Brand X Internet Services, 545 U.S. 967 (2005); United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218 (2001); Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chap. of Communists for a Great Oregon, 515 U.S. 687 (1995).

50 See, e.g., Jack M. Beermann, End the Failed Chevron Experiment Now: How Chevron Has Failed and Why It Can and Should Be Overruled, 42 Conn. L. Rev. 779 (2010); E. Donald Elliot, Chevron Matters: How the Chevron Doctrine Redefined the Roles of Congress, Courts, and Agencies in Administrative Law, 16 Vill. Envtl. L.J. 1 (2005); William Eskridge & Lauren Baer, The Continuum of Deference: Supreme Court Treatment of Agency Statutory Interpretations from Chevron to Hamdan, 96 Geo. L.J. 1083 (2008); Thomas Merrill, Judicial Deference to Executive Precedent, 101 Yale L.J. 969 (1992); Peter Schuck & E. Donald Elliot, To the Chevron Station: An Empirical Study of Federal Administrative Law, 1990 Duke L.J. 984 (1990).

51 That generalization suffices for present purposes, as it has been the case for several hundred years in America and other Anglo-American legal systems, though reaching back into far older times, criminal transgressions were such well-known and universally understood offenses as to constitute common-law crimes or ecclesiastical offenses. See, e.g., James Fitzjames Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England, vol. 1 (MacMillan 1883).

52 See, e.g., The Federalist Nos. 10 & 51 (James Madison & Alexander Hamilton).

53 See, e.g., U.S. Department of Justice, Attorney General’s Manual on the Administrative Procedure Act (1947).

54 5 U.S.C. §553(b)(3).

55 5 U.S.C. §553(c).

56 See, e.g., Thomas O. McGarity, Administrative Law as Blood Sport, 61 Duke L. J. 1671 (2012); Thomas O. McGarity, Some Thoughts on Deossifying the Rulemaking Process, 41 Duke L. J. 1385 (1992); Richard J. Pierce, Two Problems in Administrative Law: Political Parity on the District of Columbia Circuit and Judicial Deterrence of Agency Rulemaking, 1988 Duke L. J. 300 (!988).

57 See, e.g., Cass, et al., Administrative Law, supra, at 531-568; Jeffrey S. Lubbers, A Guide to Federal Agency Rulemaking (4th ed., American Bar Assn. 2006).

58 See, e.g., Associated Industries of New York State, Inc. v. U.S. Dept. of Labor, 487 F.2d 342 (2d Cir. 1973) (Friendly, J.).

59 See, e.g., Maeve P. Carey, Counting Regulations: An Overview of Rulemaking, Types of Rulemaking, and Pages in the Federal Register 5, 16-17 (Cong. Research Serv., May 2013). The annual number of rules promulgated has been in the 3,000-5,000 range since the mid-1980s. The pages devoted to rulemakings in the Federal Register account for something on the order of 40-50 percent of Federal Register pages. See id., at 16-17.

60 See, e.g., Susan Davis, This Congress Could be Least Productive Since 1947, USA Today, Aug. 15, 2012, available at http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/washington/story/2012-08-14/unproductive-congress-not-passing-bills/57060096/1; Matt Viser, This Congress Going Down as Least Productive, Boston Globe, Dec. 4, 2013, available at http://www.bostonglobe.com/news/politics/2013/12/04/congress-course-make-history-least-productive/kGAVEBskUeqCB0htOUG9GI/story.html.

61 See, e.g., American Bar Assn., Section on Criminal Law, Report of the Task Force on The Federalization of Criminal Law, at 6-11, available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/criminaljustice/Federalization_of_Criminal_Law.authcheckdam.pdf (ABA Report).

62 See, e.g., John S. Baker, Jr., Measuring the Explosive Growth of Federal Crime Legislation, 5 Engage 23 (2004) (Study for Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies), available at http://www.fed-soc.org/doclib/20080313_CorpsBaker.pdf; John Malcolm, testimony before Over-Criminalization Task Force of H.R. Comm. on Judiciary, Hearing on Defining the Problem and Scope of Over-Criminalization and Over-Federalization, Jun. 12, 2013, at 31, 32-34, available at http://judiciary.house.gov/_cache/files/e886416b-82d6-43f9-8d5d-68c44fc590cd/113-44-81464.pdf (HR Hearing: Defining Over-Criminalization). For an accessible explanation of the difficulty of coming up with an exact number, see Gary Fields & John Emshwiller, Many Failed Efforts to Count Nation’s Federal Criminal Laws, Wall St. J., Jul. 23, 2011, available at http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304319804576389601079728920?mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB10001424052702304319804576389601079728920.html.

63 See, e.g., William Stuntz, The Pathological Politics of Criminal Law, 100 Mich. L. Rev. 505 (2001).

64 See, e.g., ABA report, supra, at 10; Steven D. Benjamin, testimony before HR Hearing: Defining Over-Criminalization, supra, at 49, 57; John C. Coffee, Jr., Does “Unlawful” Mean “Criminal”?: Reflections on the Disappearing Tort/Crime Distinction in American Law,71 B.U. L. Rev. 193 (1991); Malcolm, supra.

65 See Wayne Crews & Ryan Young, Twenty Years of Non-Stop Regulation, Am. Spectator, Jun. 5, 2013, available at http://spectator.org/articles/55475/twenty-years-non-stop-regulation.

66 See Crews & Young, supra (calculations based on 2010 figures).

67 See, e.g., Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445, 458 (1927); United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U.S. 81, 89 (1921); Todd v. United States, 158 U.S. 278, 282 (1895).

68 Connally v. General Constr. Co., 269 U.S. 385, 391 (1926) (citations omitted).

69 Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507, 515 (1948). Justice Frankfurter disagreed with the application of this principle in Winters, but agreed that criminal laws “must put people on notice as to the kind of conduct from which to refrain.” Id., at 532-33 (Frankfurter, J., dissenting). See also International Harvester Co. v. Kentucky, 234 U.S. 216, 223-24 (1914).

70 See, e.g., Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733 (1974); United States v. Sharp, 27 F. Cas. 1041 (No. 16,264) (C.C. Pa. 1815).

71 See, e.g., Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 102 (1945).

72 See, e.g., Screws v. United States, supra, 325 U.S., at 138, 149-157 (Robets, Frankfurter & Jackson, JJ., dissenting); Cass, Ignorance of Law, supra, at 680-83; Herbert Packer, Mens Rea and the Supreme Court, 1962 Sup. Ct. Rev. 107, 122-123 (1962).

73 See United States v. Yates, 733 F.3d 1059 (11 th Cir. 2013), cert. granted, Apr. 2014, Docket No. 13-7451.

74 Pub. L. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (2002).

75 18 U.S.C. §1519.

76 See, e.g., Cass, Ignorance of Law, supra.

77 16 U.S.C. §§3371-3378.

78 See, e.g., C. Jarrett Dieterle, The Lacey Act: A Case Study in the Mechanics of Overcriminalization, 102 Geo. L.J. 1279 (2014).

79 See, e.g., Cass, Ignorance of Law, supra, at 689-95.

80 See Klein & Grobey, supra, at 17-32.

81 See ABA Report, supra, at 153-54.

82 See Klein & Grobey, supra, at 5-16.

83 See, e.g., Baker, supra, at 27-28.

84 See, e.g., Stuntz & Richman, supra; Terwilliger, supra.

85 See, e.g., Cass, Rule of Law, supra, at 17-18, 28-29; Dorf, supra.

86 See, e.g., Baker, supra, at 28.

87 Reports of billion-dollar-plus settlements with the government in the face of potential criminal charges—sometimes for behavior that looks like ordinary commercial decisions of the sort that might (or might not) give rise to tort liability—are symptomatic of this phenomenon. See, e.g., Danielle Douglas & Michael A. Fletcher, Toyota Reaches $1.2 Billion Settlement to End Probe of Accelerator Problems, Wash. Post, Mar. 19, 2014, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/toyota-reaches-12-billion-settlement-to-end-criminal-probe/2014/03/19/5738a3c4-af69-11e3-9627-c65021d6d572_story.html; Ben Protess & Jessica Silver-Greenberg, In Extracting Deal from JPMorgan, U.S. Aimed for Bottom Line, NY Times, Nov. 19, 2013, available at http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/11/19/13-billion-settlement-with-jpmorgan-is-announced/.

88 The reported settlement rate for federal criminal cases is 97 percent, a sharp rise over the past three decades, with the increase attributed to growing numbers of criminal laws and opportunities for increased punishment. See, e.g., Gary Fields & John Emswhiller, Federal Guilty Pleas Soar as Bargains Trump Trials, Wall St. J., Sep. 23, 2012, available at http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10000872396390443589304577637610097206808.

89 See, e.g., Lambert v. California, 355 U.S. 225 (1957); Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507, 515 (1948); Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445, 458 (1927); Connally v. General Constr. Co., 269 U.S. 385, 391 (1926); United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U.S. 81, 89 (1921); Todd v. United States, 158 U.S. 278, 282 (1895).